Two-faced: Students from immigrant families share their complex lives in between culture

- Ranee Brady

- Jun 25, 2021

- 12 min read

An American flag stands stark in front of the pastel sunset in Birmingham, AL. Photo taken by Ranee Brady.

The Yellow Tricycle and the Red Yo-Yo

Tommy Nguyen was born in Hanoi, Vietnam. When he was four, Tommy’s parents were both given scholarships to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte as international students.

His dad, Tommy said, was “always focused on going to the U.S.,” so much so that when he married Tommy’s mother, “he told her he would bring her to the U.S. with him,” though this was long before they both applied to college.

Tommy’s parents sought the opportunities that the U.S. had to offer. They wanted them for their carefree son, who rode around his warm Hanoi neighborhood on his yellow tricycle, unaware that his life was about to be changed forever.

So in 2008, two poor college students took a leap of faith, immigrating to the U.S. with four year-old Tommy along for the ride.

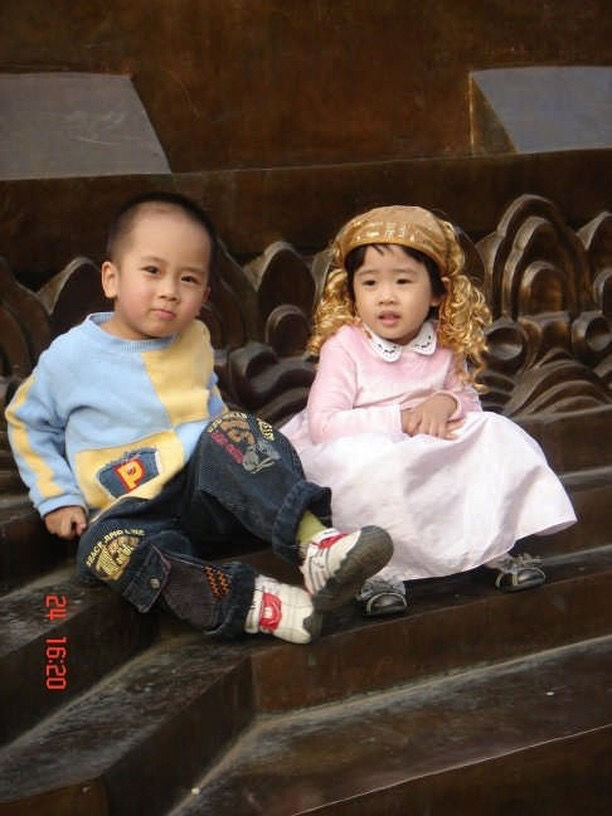

Tommy Nguyen, age 3, sits with a friend in Hanoi, Vietnam. Photo contributed by the Nguyen Family.

The first barrier in America that struck Tommy was the language.

“I really couldn't speak English,” he said, “It was scary. Everything was different. The streets are less crowded. I didn’t know anything about my neighbors. There was so much space because in Vietnam, it's a pretty small country. There were a lot of open areas that in Vietnam would be used for rice farms, but in the U.S. it's just there.”

While his parents attended college, Tommy went to pre-school at the church across from his apartment complex in Charlotte. Unlike the other kids, who were there to learn shapes, the alphabet, and numbers, Tommy was there for the sole purpose of learning english. His mom would check out book after book at the local library, trying to catch him up to his fellow classmates.

A vivid memory Tommy has of his elementary school years was of a show-and-tell. Tommy chose to bring his Disney Pixar Cars-themed yo-yo. In vietnamese, yo-yo is pronounced, “jo-jo,” so when Tommy presented this prided object to his classmates, they were quick to correct him, telling him the “correct” way to pronounce the word.

But “yo-yo” isn’t the correct way, it’s just the American way. And “jo-jo” isn’t the incorrect way, it’s just the Vietnamese way.

Some immigrant children say this is a recurring experience. They let their heritage slip in school, accidentally revealing their non-American upbringing whether it be with a mispronounced word, a cultural dish, or a clothing trademark, and then they’re told that they are “wrong”. Many of them go home after a long day of wearing a facade at school just to put on another one when they enter their house. At home, however, they can’t be too American. They have to respond to their parents in their native language, eat those cultural dishes, and wear those clothing trademarks.

Tommy’s story echoes this. His home life gradually became more and more Americanized, while he continued to have to stifle his Vietnamese-side in school. He was conditioned to blend in and to avoid anything that could have made him different.

“I think I've always tried to fit in more. Just cause it's kind of in my nature to try and fit in as best I can and to not stand out as much,” he remarked.

“Especially when I was younger, it was kind of embarrassing to not be a prototypical American,” he said. “My family's customs are different. We do things differently. I can't really relate to any of the kids talking about birthday parties and going to Disney world every year. I didn't do that. Broke college kids, you know, my parents couldn’t do that.”

Tommy’s sister, Linh, was born in 2012, three years after the rest of her family had immigrated. In 2013, Tommy’s parents graduated college and the family moved to Silverspring, Maryland, where Tommy lived until he was twelve. Then, his family moved once again to Birmingham, Alabama, where they currently live.

Now, at 17, Tommy is a rising senior at Vestavia Hills High School in Birmingham. Encouraged by his parents, Tommy takes AP classes, including Computer Science, which he plans to study in college, with a hopeful career in Engineering.

Tommy Nguyen now attends Vestavia Hills High School in Vestavia Hills, AL. Photo taken by Ranee Brady.

Tommy said he plans to revisit Vietnam in the future and reconnect with some of his roots.

“Once I get older, I'll visit,” he said. “I haven't really had a chance to go back in a long time. So, I do plan on visiting a lot more because I kind of missed out on a lot of the Vietnamese experience.”

Ultimately, though marked with struggles and bittersweet experiences, Tommy considers his unique upbringing a triumph, one that has shaped his life experiences for the better and will continue to in the future.

“I think it's pretty beneficial,” he said. “I have the edge that I come from multiple cultures. I come from Vietnamese and American culture. So I think that I have a unique outlook on life in general. I experienced a whole lot of things that most kids don’t get to experience.”

Seeds to Weeds

Kriti was born in Chicago, Illinois, where she has lived her whole life. Her father is also Indian-American and born in Chicago, like her, and his family immigrated from Chennai, India, to the United States in the sixties.

Kriti’s mother, however, was born and raised in Bangalore, India, and immigrated here much more recently. The rest of Kriti’s maternal family, including her grandparents, still live in India.

Despite being born in the U.S., Kriti's Indian heritage has had, and continues to have, a large impact on her life. She first visited India when she was one year old and even remembers getting sick when she visited because of the poor air quality in India that is often dangerous to toddlers. She even spent a few years of her childhood under the care of her maternal grandmother while her parents were busy with residencies, fellowships, and jobs.

While under the care of her grandmother, Kriti learned Tamil, the South Indian dialect her grandmother and much of her family speaks.

Kriti explains that Indian culture was much more prevalent during those years with her grandmother than American culture.

“There was an Indian garland on the doorframe, and a Ganesha knocker on the front door,” Kriti described, “I would eat a lot of Indian food.”

However, this Indian prevalence wasn’t always the case in Kriti’s life. While her family isn’t Americanized, as she grew up and attended American school and did more American activities, Kriti’s lifestyle has lost some of it’s Indian touches.

“It’s not like I go to the temple every week, I go there maybe once or twice a year,” she said. “I eat Indian food probably three times a week. I kind of understand Tamil, but I can’t speak it,” she said, no longer having the proficiency she had when she was a child.

This gradual divergence came naturally with time, but it was also catalyzed by Kriti’s life outside of her home. She said the first notable moment in which she first realized she was different from other students was when she was nine. In fourth grade, a fellow classmate approached her and said that her “skin was the color of poop.”

That moment planted a seed in Kriti, a seed similarly planted in a multitude of racially diverse children that grow up in American, predominantly white, culture. It is a seed of shame, humiliation, and self-judgement. The seed of internalized racism, Kriti called it.

Internalized racism is unintentional of course. It often goes unnoticed even by its holder. Children who are told their skin color is ugly or that they are ‘weird’ or are ‘different’ often come to believe that because they were being indoctrinated by those statements from such a young age.

“I think it’s a real thing because if someone keeps telling you you're something you're going to start to believe it,” Kriti said, “There are so many different perspectives and judgments on one group of people which creates stereotypes and sometimes we can internalize them. So yeah, I definitely think it’s a real thing.”

Kriti said a good example of internalized racism is her negative emotions she feels when she is with her grandma in public.

“Sometimes I do get a little conscious that she’s with me because she is so Indian,” Kriti admitted, “But then when I am at home with her I don’t care, I’m not conscious. I become increasingly more aware of who I’m with when I am outside with my grandma. And then when I’m at home, I’m fine because it’s my home environment. She’s my grandma.”

Internalized racism, instilled by racist peers, can create tension with even the closest of family members.

Kriti, though conditioned by years of being ashamed of her heritage, has learned to grow out of those harmful practices.

When reflecting on the situation with her grandma now, Kriti said, “She can't change herself. She can't just annihilate her Indian background for the months that she's [in the United States] and morph into this Western person and then go back to India and be her true self.”

Once a moment of shame, anger, and confusion, Kriti now remembers the moment with the boy in her fourth grade class as one of the most transformative and redefining moments of her life.

“I was able to self-reflect years later on that moment and kind of analyze what happened, and then I realized, Hey, all of these different things have been bubbling up inside me. In my head, I was saying similar things as what he said to me. And I was saying that about my Indian culture. And that was kind of like a realization point. Obviously still to this day, I might still judge myself sometimes, but I think it's important that I'm aware of that.

For some, that’s where it starts. Step one is becoming aware of your internalized racism, catching yourself before you criticize your skin, your features, or your culture.

“I’m happy that I’m Indian,” Kriti can now confidently say, “It's important to be aware of what you say to yourself, or like what you're thinking about your culture. Because if you're not aware, then you're just so stuck inside these emotions that it's almost like you're internalizing them.

Like Kriti, other immigrant children have emphasized the importance of being easy on yourself when you do become aware of your internalized racism. Remind yourself that it’s not your fault and that it’s been instilled in you from a very young age, before you even knew what racism was.

“I'm in a learning process,” Kriti said. “I'm not fully accepting of my Indian heritage every single day. But I feel like society is changing a little bit and becoming more welcoming. I think the fact that I'm being more aware is definitely making it a more positive experience. “

Hard Work Pays Off

Alice Shih LaCour was born in New Jersey, but both of her parents are from Taiwan. Alice’s mother and father immigrated from Taiwan in 1980. For the first five years of her life, Alice lived in between countries, making the 20-hour flight back and forth from Taiwan and New Jersey yearly, ultimately spending more time in Taiwan than she did in her home in New Jersey.

“It wasn't tourism,” Alice described, “I mean, we really just lived in my grandfather's apartment. And we lived everyday life there, so it was like we lived there. We didn't go to school because we were young, but we were with our cousins all the time. We went to the market. It was really like home and all we did was speak Chinese.”

People shop in the bustling markets on a cloudy day in Taiwan. Photo courtesy of Taiwan Tourism Bureau.

Alice’s visits to Taiwan gradually became less frequent as she settled into her new and unfamiliar life in America. When she was five years old, Alice’s family: her mother, father, and two brothers, moved to Georgia where Alice would spend her elementary school years. It was during these years that Alice realized just how different she was from her other classmates and just how much ahead of her she had to learn.

“I showed up at school and didn't understand what anyone was saying. Everyone looked at me strangely, obviously, because I responded in Mandarin Chinese. And my mom had to explain to my teacher that I didn't speak English.”

So while other children had their mothers teach them english from picture books like Cat in the Hat, Charlotte’s Web, and The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Alice taught herself.

“I read everything,” Alice said, “I just devoured books, and I wanted to learn everything. I would sit in the library after school for hours. Like seven days a week and check out books. And I remember the limit on checking out was 15 books. Each time I remember I would check out 15 books and it always felt like it was too few books because I wanted more books than that. And I would read through them as fast as I could, three, four days, take them back to the library and check out another 15 books.”

Her motivation was simple: she wanted to learn. She didn’t want to play catch-up with the other kids, she wanted to be the best one there.

“My goal was to learn everything and how to not just throw up my hands and say, well, it's unknowable,” she explained, “I just tried to read as much as I could and understand everyone around me.”

After elementary school, Alice and her family moved once again to Texas, where she lived during middle school and high school. Even once she learned English, there was so much more she had to learn. English was one thing to understand but American culture was a whole other story.

“I didn't know anything about pop culture,” Alice recalled, “We didn't watch movies at home. We didn't get magazines or newspapers. We didn't really watch American TV. And so when people would mention whatever was popular in the day, or they would talk about Full House, it was just like another language to me. I didn't know anything about, say American history. I didn't know the president's names. I didn't even know who George Washington was, you know? I had no idea what people were talking about. And a lot of times it made you feel like an outsider when you don't know anything about the culture that everyone else shares.”

Alice’s passion for learning and indestructible work ethic allowed her to excel in school. While other children were forced to take the more difficult class and told to complete their homework, Alice did all of that without being asked, out of her own volition, because she wanted to learn.

But this rapid adaptation to American society had adverse effects, as it does on many other immigrant children who struggle to balance two cultures and two lifestyles.

“I don't think I ever tried to be a different person,” Alice said, “but I think by necessity, you are. You’re speaking a different language and language expresses so many things differently. In school, I remember everyone would always say to me, “oh, your parents aren't from the United States. We would’ve never guessed.” And I remember feeling almost guilty about that because I wasn't trying to be someone different, but it was just no one at school could imagine what my life was like at home. And I could never really explain to my parents what school was like.”

Alice lived two lives, not intentionally, but by necessity. There was ‘school’ Alice Shih and ‘home’ Alice Shih. ‘School’ Alice Shih could never truly convey her home life to her friends and classmates, but ‘home’ Alice Shih could never truly convey her school life to her family.

“The worlds were so different,” she said. “They were apples and oranges and that in order to survive in each of them you had to be the person that could fit into that culture.”

Now reflecting on her upbringing, Alice decided that living these dual personalities was more of a blessing than a curse.

“I was completely self-motivated,” she said. “I knew there was no safety net, right? No one was going to do my book report for me because my mom couldn't read the book. So it was really down to me. And I think that's great because obviously as you grow up and you pursue higher education, no one is behind you to push you. You kind of have to push yourself.”

Alice is a woman of many traits, but selfishness is not one of them. Her motivation for all her hardwork in her life largely came from her parents and the inspiration she had drawn from them.

“For me, I think I understood the cost of immigrating to the United States for my parents,” Alice explained, “I knew that life would be easier for them if they had stayed in Taiwan. They knew their families and friends were there. It was the language they knew, they had careers back there, but the reason they were here was to give me and my brothers a better life. So I recognize the sacrifice they gave me, and I felt like I owed it to them, that I shouldn't let it go to waste.”

And waste Alice did not. Alice would go on to make her parents very proud, even if they will never fully understand all that she does. Alice attended Washington and Lee University on a full scholarship for college with a major in economics. Then, Alice attended the prestigious Yale Law School in Connecticut where she received her J.D. At 35 years old, she is now an Assistant United States Attorney and has even served on the legal counsel for the former U.S. Attorney General.

But amid all of her accomplishments, Alice remains humble and takes comfort in the simple things, especially when she reconnects with her family.

“I think it helps you have a bigger view of the world,” she said. “Everyone has a bias and that's just the way we view the world through our own lens. And I think by being an immigrant, you automatically have two lenses.”

“I think it makes me a better lawyer and a better person.”

Comments